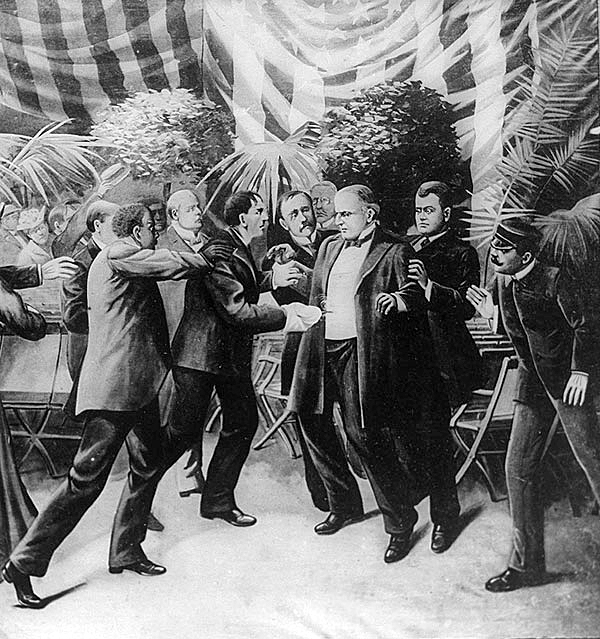

The assassination of President McKinley

On the night that John Wilkes Booth shot and killed Abraham Lincoln, the legislation to create the United States Secret Service sat on the President’s desk in the White House. At first, the organization primarily pursued counterfeiters, which at the time accounted for as much as 1/3 of all paper bills in circulation, and over time also combated other federal crimes including murder, robbery, and racketeering. After the assassination of President William McKinley in September of 1901—the third Presidential assassination in less than forty years—the Secret Service also undertook the responsibility of providing personal protection for the Chief Executive, his immediate family, and visiting or foreign dignitaries.

The first American President to make use of Secret Service protection was therefore McKinley’s successor, former Governor of New York and war hero Theodore Roosevelt. One of the President’s closest bodyguards was 6’4” Scotland-born William Craig, age 47. After serving for 12 years in the British military (during which time it was said that he guarded Queen Victoria), Craig emigrated to the South Side of Chicago, and from there accepted a position within the Secret Service in 1900. During the time that he had provided personal protection for the Roosevelt family, Agent Craig and the President, who were only three years apart in age, had grown close to each other, and ‘Big Bill’ was also a favorite of the President’s children, who at the time ranged from ages 4 to 17.

A barouche

Slightly less than a year after taking office, President Roosevelt toured the states of New England in order to support the local Republican candidates in advance of their upcoming election. On the morning of September 3, 1902, he delivered a speech in the far western Massachusetts village of Pittstown and, after a brief visit with respected ex-Senator Harry Dawes, departed to the southwest toward the neighboring town of Lenox, where the President had a planned speech to deliver at noon. The day was bright and sunny, with the late summer foliage still thick on the trees, so the party anticipated a smooth and pleasant trip with few complications.

President Roosevelt (l.) and Governor Crane (r.)

George Cortelyou (l.) and William Craig (r.)

The President rode in a barouche, a type of open-top carriage that seated four, that was pulled by four gray horses. President Roosevelt sat in the back seat, beside Massachusetts Governor Winthrop M. Crane, while George Cortelyou, Secretary to the President Roosevelt and to President McKinley before him, sat alone in the front seat of the carriage, facing toward the rear. On the left side of the carriage’s front bench, livery owner David J. Pratt of Dalton, Massachusetts, drove the team of horses, while Agent Craig sat at the right side of the elevated perch. The barouche left Pittsfield at about 10:00 in the morning, and with its mounted escort, made good time down the cobblestones of South Street, the horses prancing at about 6 miles per hour toward Lenox.

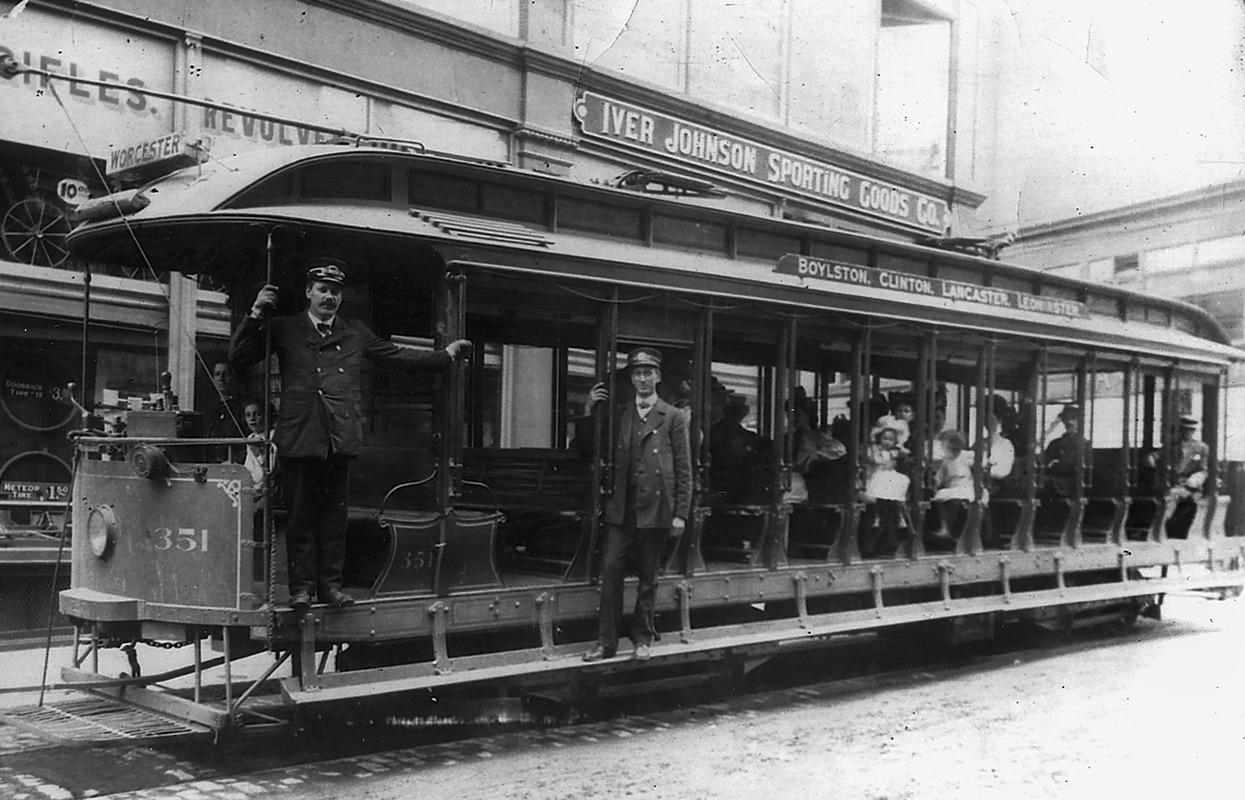

Meanwhile, James W. Hull, Director of the Pittstown Electric Street Railway Company, enlisted one of his company’s streetcars so that he and several visiting dignitaries could follow the President during the day’s events. The President’s security detail had ordered the trolley service to have been shut down that day, but the news either did not reach, or was ignored by, Hull, along with the trolley’s conductor James Kelly and its motorman (that is, driver) Euclid Madden. Hull had planned for the trolley to shadow the President’s carriage during the trip to Lenox, but delays in boarding prevented the trolley’s departure until about fifteen minutes after the President’s barouche had left Pittstown. With eager passengers exhorting him to make up the time, Madden piloted his massive and motorized trolley down South Street at about 15 to 25 miles per hour, about three or four times the speed of the President’s horse-drawn carriage.

Soon, the congested journey through town melded into a pleasant country ride through the hills and woodlands of rural Massachusetts, and the crowds thinned from a packed throng of well-wishers to scattered pockets of curious and cheering residents. The President’s entourage passed the Pittstown Country Club, and rode in the shadow of South Mountain, at the foot of which the road took a sharp turn to the right. As the road curved, the trolley tracks—which usually run down the center of the road—offset to the left side, then crossed to the right at the apex of the curve, then back to the left before straightening out, in an attempt to make the curve less severe for the heavier trolleys.

The President’s barouche entered the curve, crossing the tracks for the first time with ease, but as it pulled out of the curve and crossed the tracks a second time, Euclid Madden’s speeding trolley—its approach masked by the drastic curve and thick foliage—smashed into the right side of the carriage without warning, scraping down the side and mangling both wheels with thunderous force. President Roosevelt and Governor Crane were launched about thirty feet through the air into a clear patch on the far side of the road, with the President landing on his face in the mud. The trolley drug the mashed carriage to a screeching, twisted stop as one horse, gravely injured in the collision, collapsed to the ground, screaming in pain. The other three horses broke from their reins and bolted.

The President's wrecked barouche

The President quickly found his glasses, which had been flung from his head, and rose quickly, asking loudly about the others in his party. His lip bled from where it had hit the carriage on the way out, and a massive bruise was growing along the entire right side of his face; his coat was torn and his silk hat was dented and bent and covered in mud. Governor Crane, as it turned out, had landed even more fortuitously than the President had, and was entirely unhurt, and though Secretary Cortelyou was out cold and bleeding from the neck, his injuries proved to be minor, also thanks to the muddy bank which broke his fall. The Driver, Mr. Pratt, was seriously injured by his fall; he was bleeding from both ears, and he appeared in grave condition, but Agent Craig had absorbed the worst of the crash. From his unsecured and elevated seat on the side of the collision, the Secret Service agent had been knocked directly into the path of the trolley and killed instantly; the bulk of the trolley had crushed his skull, and the speeding metal wheels had ground his chest and abdomen into the track for some distance.

The President was furious. Still covered in blood and mud and his face rapidly swelling, he demanded the identity of the trolley driver; when Euclid Madden stepped forward, President Roosevelt howled in fury, accusing Madden of abject negligence and, as a newsman later understated, “used forcible language in expressing his displeasure.” Madden insisted that he had the right of way; Roosevelt shook his fist and hollered through blood-stained teeth, “This is the most damnable outrage I ever knew!” By all accounts, the situation likely would have come to blows had bystanders not intervened between the two men, dragging them in opposite directions, each continuing to protest.

Driver David Pratt was taken to the House of Mercy in Pittsfield, where he eventually recovered from a dislocated left shoulder, a sprained ankle, and various cuts and bruises. Agents Craig’s body was extricated from the wreckage and taken to the house of local resident A.B. Stevens; President Roosevelt, Governor Crane, and Secretary Cortelyou also followed to the same house, where they considered how to proceed after the tragedy. The President refused to cancel the rest of his trip, although he said he would not deliver any more speeches that day. A replacement carriage arrived after about a half hour, and the party continued to the Aspinwall Hotel in Lenox, where Roosevelt delivered a short explanation to the crowd, apologized for the abrupt cancellation, and retired to his room in silence.

President Roosevelt praised and mourned William Craig publicly numerous times; he later discovered that he had also severely injured his shin during the accident as it collided with the carriage frame; the severe leg pain that resulted required surgery and plagued him for the rest of his life. Governor Crane served for another year in his executive position; his successor then appointed him as US Senator from Massachusetts, where he served from 1904 until 1913. In addition to his later posts of Postmaster General and Secretary of the Treasury, George Cortelyou revolutionized many procedures for White House protocol and press access that survive to this day. Euclid Madden and James Kelly both pleaded guilty to manslaughter; on January 24, 1903, Judge Pierce of Fitchburg released Kelly but sentenced Madden to a hefty fine and six months in jail; the Pittstown Electric Street Railway Company covered the $500 fine in full and paid Madden his full wage while he was serving his time, after which he was welcomed back to work.

In 1908, President Roosevelt ordered Attorney General Charles Bonaparte to create what would later become known as the Federal Bureau of Investigation, which ultimately took over many of the Secret Service’s federal law enforcement responsibilities. The Secret Service, however, retained its focus on Presidential protection as well as the pursuit of counterfeiters, and in the latter role remained a subsidiary of the Department of Treasury until it was reorganized under the newly-formed Bureau of Homeland Security in 2001. In 2002, on the hundredth anniversary of his death, the Secret Service honored the sacrifice of William ‘Big Bill’ Craig, the first Secret Service agent to lose their life while protecting the President, with a ceremony and a new headstone at his Chicago gravesite.

A trolley similar to the one driven by Euclid Madden

Links and Sources:

“President’s Landau Struck by a Car”, New York Times, September 4, 1902, p. 1.

“Craig Inquest Begun”, New York Times, September 10, 1902, p. 3.

“Six Months in Jail and a Fine”, The Sacred Heart Review, January 24, 1903, p. 1.

“Motorman Who Killed Craig Gets Six Months”, The Standard, Vol. LII, January 1, 1903 to July 1, 1903, p. 89.

“Day 83: Euclid Martin”, by Brian Sullivan, The Berkshire Eagle, Berkshire, Mass., March 24, 2011.

The American Law Review, vol. XXXVI, Review Publishing Co., St. Louis, 1902, p. 747-748.

The Electrician, vol. L, London, 1903, p. 129.

Theodore Rex, by Edmund Morris, Random House, 2001.

Photo of streetcar from the Lancaster (MA) Historical Society via Digital Commonwealth.

Photo of Secret Service from the Library of Congress via CBS News.

Photo of wrecked barouche from the Theodore Roosevelt Collection, Harvard College Library.

“The Trolley and the Barouche” © 2015 by James Husband