Elsie and Archie Mitchell

"Look what I found, dear!"

On May 5, 1945, Elsie Mitchell shouted these words back to her husband Archie, as he returned from parking the car for their church outing in Bly, Oregon. Elsie, a pregnant 26-year-old Sunday school teacher, and five teenaged students approached the oddity they had found, half buried in a late-season snowbank. Someone shouted that it was a balloon, and one or more of the children tried to drag it back to a more open area. Archie Mitchell, a local pastor, had heard of explosive-laden balloons spotted near the west coast. He yelled back for them not to touch it, but it was too late, and the balloon contraption exploded, sending flames into the air and shaking the ground.

Archie ran full speed toward his wife and the children, but by the time he reached them, Elsie and all five students—Dick Patzke (14), Jay Gifford (13), Edward Engen (13), Joan Patzke (13), and Sherman Shoemaker (11)—were lying motionless around a smoking one-foot crater. Archie tried to extinguish Elsie's burning dress with his bare hands, but could not. The blast had killed Elsie and four of the students immediately; the fifth survived for only a few minutes. They had no way of knowing it, but those six civilian Oregon picnickers had just become the only wartime casualties on the American continent due to enemy action in World War II.

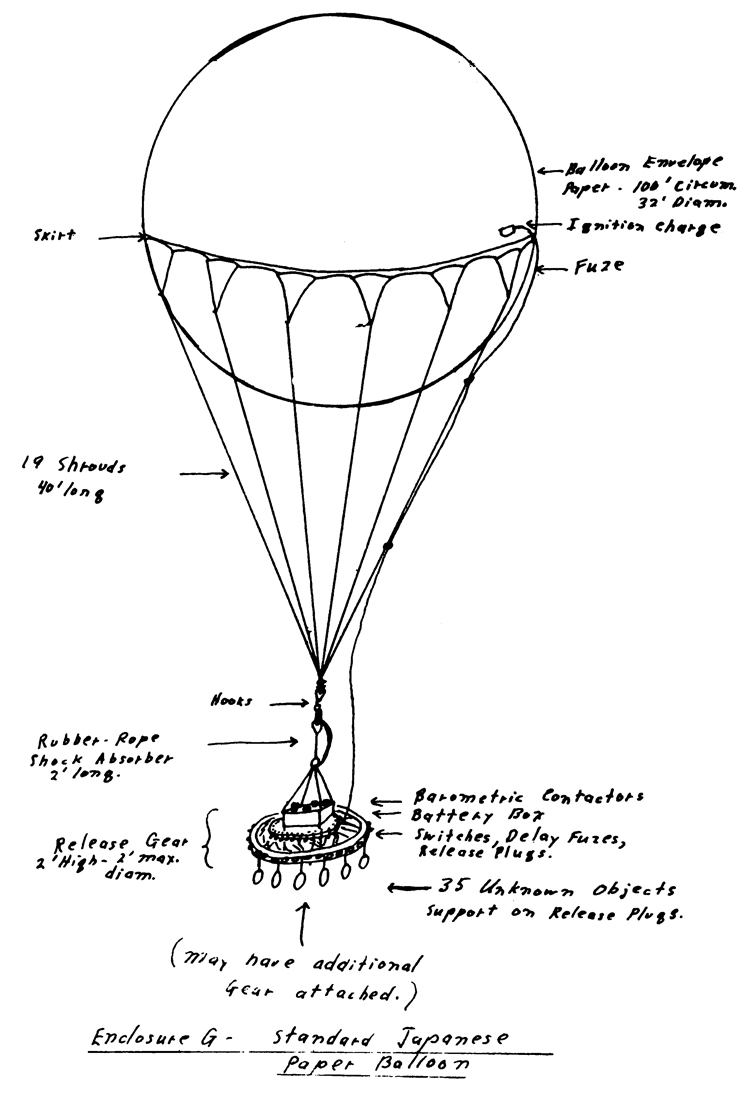

The explosive balloon's story begins about a year earlier. By 1944, the Empire of Japan held the unenviable position of being involved in a large-scale war against a powerful opponent with massive industrial resources. In their attempt to find economical but effective ways to inflict damage on the United States homeland, Japanese scientists devised a method to use the recently-discovered Pacific jet stream—a high-altitude river of air which crossed from Japan across the Pacific Ocean to North America—to their advantage. Japanese scientists developed a plan to create a series of 70-foot-tall hydrogen balloons made from mulberry paper and sealed by potato flour, each carrying a 33 pound incendiary bomb. The balloons were assembled mostly by teenaged girls and relied upon a complex system of weights and ballast using an altimeter, rotating wheels, and sandbags to keep the balloons aloft during their three-day floating journey. These airborne bombs were called Fu-Go, or "fire balloons".

From November 1944 until April 1945, the Japanese launched over 9,000 of these balloons, with the hopes that they would cause casualties, burn down forests and farmland, and cause panic in the United States and Canada. The first balloon was spotted near San Pedro, California, on November 4, 1944, but their source was unknown at the time. The U.S. Office of Censorship asked that news of them not be printed or spread, with the hopes that whoever made the bombs would lose interest in the program if they did not see any evidence of it working, but sporadic rumors reports persisted. The deaths of Elsie Mitchell and the five students inspired a change in the policy of silence, and the media began to spread government warnings for civilians to be wary of the floating bombs.

In order to determine their precise point of origin, American forensic scientists investigated the balloons, concentrating on the makeup of the sand used as ballast. They provided samples to Col. Sigmund Poole of the US Geological Survey's Military Geology Unit; upon receiving the samples, he reportedly asked, "Where'd the damn sand come from?"

Forensic geologists within the MGU quickly determined that the sand could not have originated in North America. Furthermore, the absence of coral or mica but the presence of igneous augite and hypersthene, metamorphic hornblende and garnet, and a microscopic skeletal organisms called forams led the analysts to determine that the source was a northern Pacific island that had once been connected to the mainland, qualifications which describe the islands of Japan accurately but not exclusively. Comparison to an 1889 scholarly paper specifying geological findings from northern Japan narrowed the search specifically to one of two beaches on the northeastern coast of Honshu, not far from Tokyo itself. Subsequently, American bombers identified and destroyed two of the three helium factories and several sources of other balloon parts.

The Japanese would not learn of any chaos they were hoping to create during the war; the widespread forest fires and crop damage never materialized, although there were several harrowing near misses, including a dud landing near an atomic bomb construction site, others failing to explode despite touching down near power lines or manufacturies, and one Washington state boy carrying one of the bombs around for several days before authorities took it from him, presumably to his profound disappointment. News of the deaths in Oregon never reached the Japanese General Staff; if it had, according to former engineer Kiyoshi Tanaka, they certainly would have launched another 10,000 of the Fu-Go without hesitation. Disillusioned, the Japanese discontinued the program.

Although Japan launched between 6,000 and 9,000 of the balloons, fewer than 400 have ever been found; the remainder may have been lost at sea or disintegrated, but others may have landed in remote locations of the American and Canadian wilderness, where they remain to this day. For those interested, the Department of the Navy has recently declassified a video detailing many of the technical aspects of the balloons, which is available here.

Links and Sources:

"How Geologists Unraveled the Mystery of Japanese Vengeance Balloon Bombs in World War II", by Dr. J. David Rogers , Missouri University of Science and Technology, retrieved March 14, 2012.

"Blast Kills 6, Five Children, Pastor's Wife in Explosion: Fishing Jaunt Proves Fatal to Bly Residents," Klamath Falls Herald and News, May 7, 1945.

"Japanese Balloon Bomb Killed 7", from the Southern Oregon Mail Tribune, November 22, 2009.

"Balloon Bombs" in the Oregon Encyclopedia, retrieved March 14, 2012.

"Japan's Secret WWII Weapon: Balloon Bombs", in National Geographic, May 27, 2013, available here.

An Introduction to Forensice Geoscience, by Elisa Bergslien, Wiley-Blackwell Publishing, Oxford, 2012.

Diagram of balloon is from Japanese Balloon and Attached Devices, by the Technical Air Intelligence Center, Naval Air Station, Anacostia, DC, May 1945.

Photo of memorial plaque courtesy of the Southern Oregon Visitors Association.

Map of balloon bomb landing sites by Jerome R. Cookson of National Geographic.

"Floating Bombs" © 2015 by James Husband.