On January 3, 1762, Samuel and Esther Ransom of Canaan, Connecticut, had a son, and they named him after Samuel's best friend and neighbor, George Palmer. In 1773, the family—both parents and eight children, including 11-year-old George—emigrated as part of a widespread migration of Connecticut settlers to what is now northeastern Pennsylvania, settling near the town of Wilkes-Barre in Wyoming Valley. In September 15, 1776, 14-year-old George enlisted with his father and brother-in-law into the 2nd Westmoreland (Wyoming) Independent Company to fight in the American Revolution. His first position there was to bury the dead.

George fought with his father in his unit's first engagement, the Battle of Millstone, on January 20, 1777, near Manville, New Jersey. In this conflict, about 450 Patriot militia under General Philemon Dickinson waded through waist-deep icy water to defeat a British foraging party of roughly equal size, capturing about 50 prisoners, 50 wagons full of supplies, and 100 or so horses. The Patriots lost only a single man, and Gen. Dickinson allowed his troops to share in the spoils. One British witness later insisted that the attackers were too well-trained to be militia, even though they were, as it happened, exactly that.

Washington and Lafayette at Valley Forge

George also fought with his father at several other key battles in 1777. On April 13, a force of British and Hessian soldiers under General Sir Charles Cornwallis attacked and defeated a force of Patriots led by General Benjamin Lincoln in the Battle of Bound Brook, on New Jersey's Atlantic shore; the garrison was routed, but the British could only plunder the area before being forced to flee by Patriot reinforcements. The Battle of Brandywine in Chadds Ford Township, Pennsylvania, saw the Army of General George Washington suffer defeat at the hands of British General Sir William Howe on September 11, forcing the Patriots back to Philadelphia. Gen. Washington suffered a second defeat on October 4 in the Battle of Germantown, a section of Philadelphia, ensuring that the British would control the city throughout the upcoming winter. The Siege of Mud Island Fort persisted until November 16, when the defending Patriot forces were forced to cede what is now Fort Mifflin to the British, strengthening the Loyalist hold on the city. The defeat forced Gen. Washington to retreat the Patriot forces to Valley Forge, where they remained through the dreadful winter of 1777-1778, during which time starvation and exposure killed nearly 2,500 soldiers. The Ransoms survived the plight, as George celebrated his sixteenth birthday in the camp.

The Battle of Wyoming, July 3, 1778

In 1778, news reached the Patriot forces that Wyoming Valley was under threat of attack by Canadian Loyalists and their Indian allies, and George's father, by that point a Captain, resigned his post to return to Wilkes-Barre to defend his homestead. George elected to remain with his unit and therefore was absent as a combined force of Tory militia and Iroquois warriors killed more than 300 Patriot defenders, including Capt. Samuel Ransom, in the Wyoming Valley Massacre on July 3 of that year. George arrived the following day, after having hurriedly marched back with other Luzerne County men; he identified his father's decapitated body by recognizing his distinctive silver shoe buckles. Following the battle, George obtained a furlough and spent the following winter with his mother, in the red Ransom house on Garrison Hill, the two subsisting solely on the milk of a single cow.

In 1779, George transferred to the command of Captain Simon Spaulding in the Army of General John Sullivan, which Gen. Washington then sent against the Indians in the Lake Country of New York. On August 29, the Campaign of Sullivan dealt a decisive victory to the Tories and Indians in the Battle of Newtown on the Chemung River in upstate New York; the Continental army then destroyed more than 40 Iroquois villages in retaliation for their attacks. George Ransom later termed that experience as “bashing the Indians,” and by the end of the Revolution, he had attained the rank of Orderly (that is, First) Sergeant.

With the war concluded, George, now 19 years old, returned to his home in Wyoming Valley. On December 6, 1780 George visited the house of Benjamin Harvey on the outskirts of Wilkes-Barre, along with Mr. Harvey's 17-year-old son Elisha and daughter Louise, and a friend, Lucy Bullworth. George's intention that night was to court one of the young ladies (sources are unclear which), and so he wore his finest dress uniform. As the group spoke around the fireplace, a raiding party of Indians approached the house, and one used his tomahawk to knock on Mr. Harvey's front door. Realizing what was happening but intending to avert trouble, Mr. Harvey opened the door, and the Indians burst into the home, seizing and binding all five attendees before escaping with their captives to nearby Shawnee Mountain. After some consultation, the Indians painted the two ladies' faces and released them into the darkness, with instructions to warn Colonel Zebulon Butler, the commander of the local militia forces, of the Indians' presence. By the time the ladies reached the town of Wilkes-Barre the next morning, the raiding party and their three remaining captives—George, Elisha, and Mr. Harvey —were long gone.

The Indians intended to sell the three men, but after some marching north along the Susquehanna River, they realized that Mr. Harvey, who was nearly 70 years old, would not survive the journey. Instead, the oldest Indian tied their elderly prisoner to a tree while several of the younger tribesmen began a round of target practice, taking turns throwing their tomahawks at Mr. Harvey's head. After several miraculous misses on the parts of the young braves, the elder Indian decided to let Mr. Harvey go; the younger warriors protested, pleading for more chances to improve their aim, but the older Indian had apparently reasoned that the Great Spirit had spared the prisoner's life. Mr. Harvey headed south along the river for several days, eating a stray dog along the way for sustenance, until he happened upon a boat which took him back to Wilkes-Barre. Meanwhile, the raiding party continued north, with George and Elisha still in tow.

The Indians soon discovered that George was a talented shot with a musket, and they demanded that he kill several horses for food during the journey, which he did; as payment, the Indians rewarded George with salt for his dinner. Eventually, the Indians transferred George—presumably still in his finest, but ragged, dress uniform—to the British in Montreal, while Elisha remained with the Indians. Elisha remained with the Indians through the winter, and was later sold to a Scotsman for a half barrel of rum; two years later, he returned to Luzerne County as the result of a prisoner exchange orchestrated by his father, who had worked tirelessly since their capture to secure his son's return.

Coteau-du-Lac on Prison Island

Meanwhile, in February of 1781, the British moved George and 166 other Patriot prisoners 45 miles up the St. Lawrence River to a blockhouse at the canal fort of Coteau-du-Lac, Quebec, which the English simply called Prison Island. While there, the lead guard—a despotic 18-year-old Scottish soldier named MacAlpin—would routinely demand the prisoners shovel snow; each prisoner refused in turn, and MacAlpin had them all systematically chained in irons as punishment. George Ransom and William Palmeters were the last two asked, and when they also refused, MacAlpin had them placed in an open, floorless house overnight, to freeze in the biting Canadian winter air. The following morning, MacAlpin expected their spirits to be broken, but when he demanded again that they shovel the snow, George bellowed, "Not by order of a damned Tory!"

MacAlpin then had George and William shackled and moved to another building, but while there the colonial men convinced Charles Grandison, a black fiddler among the captives, to play while they danced jigs and reels all night. MacAlpin, discouraged by the unfazed morale of the prisoners, demanded Grandison play for him, but the fiddler refused as long as his fellows were chained up, maintaining his resolve even after MacAlpin had him subsequently lashed. MacAlpin continued this abuse throughout the winter, stringing up or flogging captives, but none of the Patriot prisoners consented to shovel the snow.

In early June, George and two of his fellow captives, John Butterworth and John Brown, began periodically sneaking away from their work detail to construct a makeshift raft. They lashed together scrounged parts while out of sight of the British guard and when called away, they buried their half-completed construct in the sand. On June 9, the three men sailed the raft—so non-seaworthy that its passengers' weight caused it to sink about a foot below the water—across the St. Lawrence River to the southern shore. Exhausted by the hard rowing, they nonetheless headed south into the wilderness toward Lake Champlain.

Lake Champlain, New York

Despite having no warm clothes, only about a half a days' rations, and being faced with rough and unfamiliar terrain, the escapees reached Lake Champlain in two days' time, sustaining themselves on captured snakes and frogs. From there, they continued toward Vermont, at one point convincing a sympathetic but poverty-stricken old woman to allow them each three swallows of milk and a haunch of bread. After three more days of punishing travel, they finally reached the village of Putney, Vermont, where George's uncle lived. From there, Butterworth and Brown headed toward Albany, while George walked south to Litchfield, Connecticut, near the town where he was born, and ultimately back to Wilkes-Barre.

After regaining his health, George rejoined the militia, remaining in the command of the 1st Connecticut Regiment until it was discharged at West Point in 1783. On August 14, 1783, at the age of 21, he married 23-year-old Olive Utley; they lived in Taunton, Massachusetts at first, where they welcomed a daughter, Sarah, in 1784, but by 1786, they were back in Luzerne County, where they had a second daughter, Louisa. In 1787, George was promoted to Captain of the 7th Company, 3rd Regiment of the Luzerne Militia, under Lt. Col. Matthias Hollenbeck, and the couple then had a third daughter Esther in 1788, and a son, George Jr., in 1791. By this time, George had acquired his father's lands from his brothers and sisters via quitclaim. Olive died on July 14, 1793 at the age of 33, leaving George a widower with four small children.

Less than six months later, on January 9, 1794, George, aged 32, remarried to Elizabeth Lamoreaux, the 17-year-old daughter of Thomas and Katurah Lamoreaux of Monroe County, New York. Together, they had thirteen more children—Samuel, Olive, William, Elizabeth, Keturah, Lyvia, Thomas, Chester, Eleanor, Miner, Lydia, Amelia, and Ira—between 1795 and 1822; all but Eleanor survived to adulthood. By the time Ira was born, his parents were 60 and 45, and his oldest half-sister was already 38.

The Ransom House

George continued to acquire additional acreage in Jackson and Lehman Townships; a deed shows that he paid for a large area that is now Lehman Center, establishing a thriving timber and sawmill business. In 1799, George was promoted to Lt. Colonel and became the fourth Commander of the 2nd Battalion,3rd Regiment of the Luzerne County Militia, the local unit of the Pennsylvania militia; today, that unit is the 109th Field Artillery of the Pennsylvania National Guard, based in Kingston. He continued to serve at West Point and drilled soldiers in preparation for the War of 1812. For his service, he earned the Badge of Merit, which was at the time the highest military honor, and his discharge papers were personally signed by Gen. Washington. On April 29, 1824, he lost his 33-year-old oldest son, George Palmer Ransom Jr., when some logs rolled over him during a logging operation; five years later, George's daughter Elizabeth also died at the age of 30.

Later in life, as Colonel Ransom was advanced in years—the exact date is unknown—he overheard a young man criticized General Washington; in response the Colonel knocked the boy to the ground with his cane. Colonel Ransom denied a lawyer for his court date, and the presiding Judge Hollenback ask where the Colonel was in 1777, in July 1778, in summer of 1779, and in the winter of 1780. Colonel Ransom answered honestly: He was in Washington's Army, heading back to the Wyoming Valley, in Lake Country with General Sullivan, and a prisoner on the St. Lawrence, respectively.

"And did you knock the fellow down, Colonel?" asked the judge.

"I did so, and would do it again under like provocation," Colonel Ransom replied.

"What was the provocation?"

"The rascal abused the name of General Washington."

Judge Hollenback had heard enough. Colonel Ransom was fined a charge of one penny, and the young man was required to pay the court costs. The observers in the court applauded.

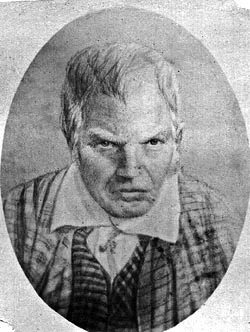

George Palmer Ransom, later in life

Colonel Ransom established himself as a prominent man in the Wyoming Valley, and continued to live in his large red house on Garrison Hill in Plymouth until well into his eighties, using two canes to get about. George died on September 5, 1850, in Plymouth, one of the last remaining Revolutionary War veterans in the valley, and was buried with military honors in Shupp Cemetery in Plymouth. Chronicler Hendrick B. Wright remembers Colonel Ransom as "a stout built, square-shouldered man about five feet eight inches high, light complexion and blue eyes. He had a pleasant and agreeable manner, very communicative, and was a most obliging neighbor. He was a man who liked mirth, and nobody enjoyed a joke better than he. He was quiet and peaceable; a man of thoroughly domestic habits. He raised a large family of children and brought them up respectably, giving them all a good common school education. His house was always open to hospitality, and no man more thoroughly and keenly relished a convivial assemblage than he. He possessed the highest sense of honor. His long training in the revolutionary service made him very punctilious in his intercourse. His word was his bond.” George Ransom was a man of “many virtues, and whose strong arm and resolute will had made their impression in the frame work and superstructure of Free and Republican America.”

Elizabeth died on August 27, 1859 at the age of 82, and was buried with her husband. In 1903, the Ransom family was re-interred in the Shawnee Cemetery, above the ravages of the river and railroad and mining operations. Every Memorial Day, the local chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution decorates George’s grave, which is still flanked by those of his wives Olive and Elizabeth.

Links and Sources:

Historical Sketches of Plymouth, by Hendrick B. Wright, Philadelphia, Penn., 1873.

A Geneological Record of the Descendants of Captain Samuel Ransom of the Continental Army, by Captain Clinton B. Sears, Nixon-Jones Printing Co., St. Louis, 1882.

Drawing of Col. Ransom was in Prominent Men: Scranton and Vicinity, Wilkes-Barre and Vicinity, Pittston, Hazleton, Carbondale, Montrose and Vicinity, Pennsylvania (1906).

Detail of the painting of the Wyoming Massacre by Alonzo Chappel, 1858, is in the public domain.

Image of the upstate New York Wilderness "Willsboro Bay from Rattlesnake Mountain" by TourPro, accessed via Google Earth.

"George Palmer Ransom" © 2015 by James W. Husband