During World War II, Harley-Davidson produced nearly 100,000 motorcycles for the military motor pools of the United States and other Allied forces. Riding a post-war wave of popularity and prosperity, Harley advertised its powerful, V-twin models with images of smiling, clean-cut couples touring the American countryside. This image did not last.

For the July Fourth weekend of 1947, the American Motorcycle Association chose Hollister, California, a largely agricultural town of about 4,500 in the center of the state, as the destination site of one of their "Gypsy Tours", in which many established motorcycle clubs from across the country staged a long-distance ride, culminating in a rally with their fellow enthusiasts. Hollister had hosted Gypsy Tours, races, hill climbs, and other events before, to the local merchants' great delight, and the locals accommodated the biker lifestyle. The town had only six police officers to patrol its 27 bars and 21 gas stations, but had no reason to believe that any trouble would arise.

In the years following the end of World War II, many of the war's veterans struggled to re-adapt to the pre-war ideals of daily life. The accepted routines of a steady job and a domestic home life were not meeting the needs of the returning soldiers. Instead, many of them turned to motorcycle clubs, spending their days on the road with wind in their hair, enjoying the feeling of outdoor freedom. Many returning soldiers also drank quite a bit, often in an attempt to mentally cope with having been at war.

Several thousand of these bikers gathered in Hollister over that weekend; many of which had started drinking days before their arrival. The town was soon immersed in a fairly wild party of drunken motorcyclists, including one who rode his motorcycle up the stairs of a local watering hole, burst through the door, and parked right at the bar to order a drink. The local hospital admitted about 60 people, mostly for the repercussions of their own drunken stunts. Drunks quickly filled the jail, and police mistook one, nicknamed Wino Willie from the Boozefighters cycling club, for trying to incite a riot.

The anarchy soon overwhelmed Hollister's modest police force, and they called for help from the California Highway Patrol, who responded by sending 40 CHP officers for crowd control. Most of the bikers, being military veterans, took well to being given orders by the police and cooperated by moving the party to the edge of town. One quick-thinking Lieutenant enlisted a local band to set up on a flatbed truck and play music to get the bikers dancing (and therefore distracted); meanwhile the Hollister Chief of Police had the bars close two hours early. The party wound down, and everyone went home to sleep it off.

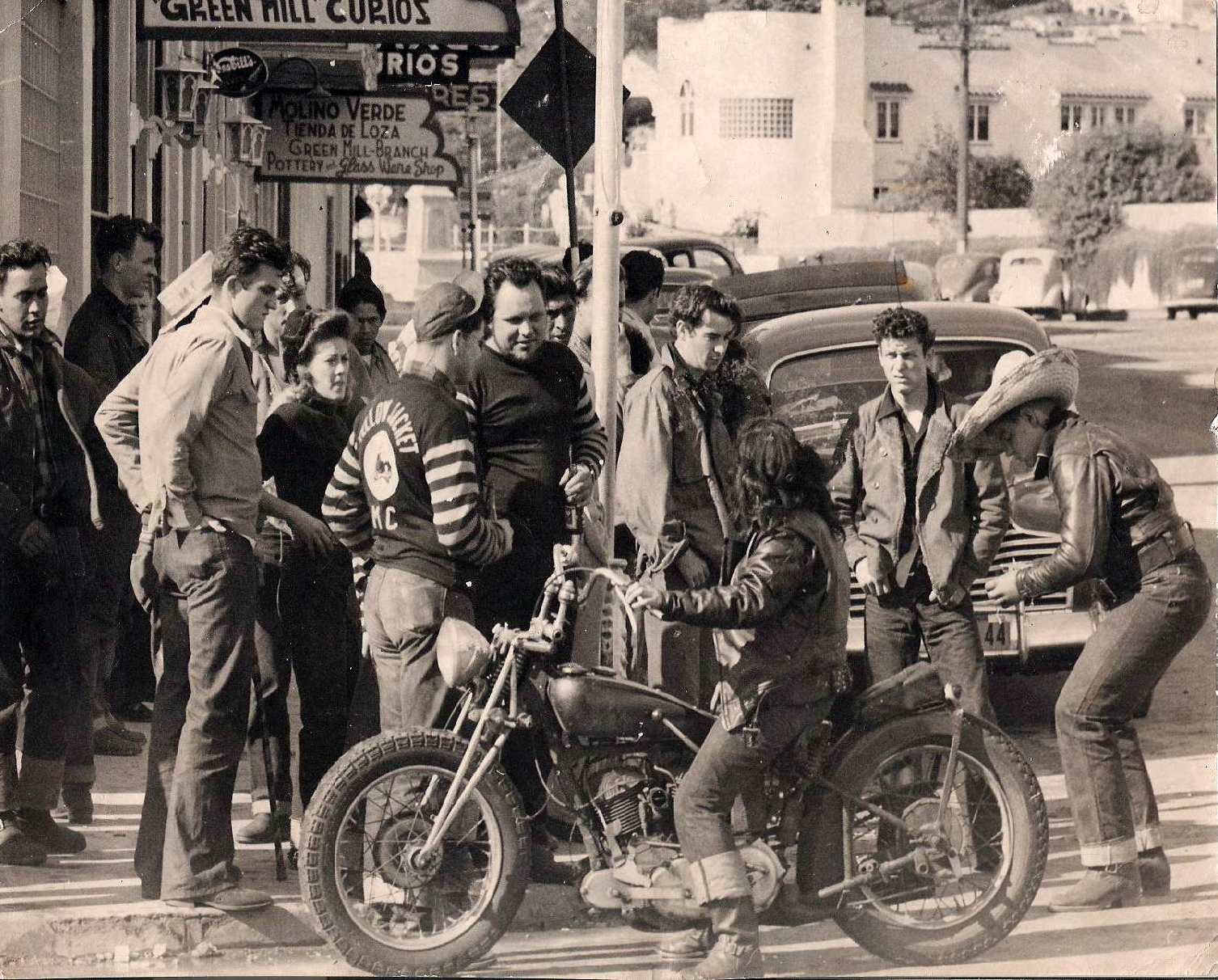

Peterson's photo of Eddie Davenport

The Hollister Gypsy Tour would have faded into memory, were it not for a San Francisco Chronicle photographer named Barney Peterson. Peterson wanted an attention-grabbing photo, but had arrived late, and missed most of the festivities; to get his photo, Peterson, although surrounded by hordes of stumbling drunks and roaring motorcycles, decided to stage his own shot. He and an associate kicked a pile of discarded and broken beer bottles out of a nearby alley and distributed them around a Harley-Davidson EL Knucklehead motorcycle parked in front of Johnny's Bar and Grill on San Benito Street. Peterson then grabbed a drunken biker named Eddie Davenport, apparently at random, and convinced him sit on the motorcycle for a picture. While the resulting image was not doctored or manufactured, it was certainly deceptive in its portrayal of the bikers; Peterson told Davenport where and how to sit, on a motorcycle that wasn't his, and his jacket was strategically placed on him. Peterson snapped several frames, one of which shows the bottles arranged neatly in a row on the curb, and went on his way, satisfied with his photographs.

The Chronicle passed on the photo, but it ran a short story about the affair, using words like "terrorism" and "pandemonium" in its description of the weekend. Life Magazine, however, put Peterson's photo on the cover of its July 21, 1947 issue, and printed a story entitled "Cyclist's Holiday: He and Friends Terrorize Town", highlighting and exaggerating the lawlessness of the Hollister Gypsy Tour. Soon, the Gypsy Tour became known, somewhat hyperbolically, as the "Hollister Riot", and the press appropriated the term "outlaw biker" (which originally meant a club not registered with the AMA) to describe a new breed of lawless, feral madmen, roaming the wilds of the US heartland.

Motorcyclists protested the depiction of their sport, but to little avail. "Cyclist's Holiday" was followed in 1951 by the fictional account "The Cyclist's Raid" in Harper's Magazine, and that in turn led to the 1953 movie The Wild One, in which Marlon Brando's rebellious protagonist and Lee Marvin's bestial villain solidified the concept of the dangerous Harley rider in the minds of the public. Even now, the general public often associates the image of the classic Harley rider with criminal violence, roguery, and a sense of lawless abandon, the ultimate result of an opportunistic photographer's misrepresentation of a California party weekend as a vicious, anarchic siege.

Links and Sources:

Dulaney, William L., "A Brief History of 'Outlaw' Motorcycle Clubs", in the International Journal of Motorcycle Studies, November 2005, accessed April 5, 2012.

Biker Gangs and Organized Crime, by Thomas Barker, Elsevier, 2007.

The Original Wild Ones: Tales of the Boozefighter Motorcycle Club, by Bill Hayes, Jim Quattlebaum, and Dave Nichols, MotorBooks International, 2009.

One Percenter: The Legend of the Outlaw Biker, by Dave Nichols and Kim Peterson, MotorBooks International, 2010.

Biker: Truth and Myth, by Bill Osgerby, Globe Pequot, 2005.

Outlaw Machine: Harley-Davidson and the Search for the American Soul, by Brock Yates, Broadway Books, 2000

"The Hollister Gypsy Tour" © 2015 by James Husband.