In 1810, the owner of the Horse Shoe Brewery in London, built a 22 foot high beer fermentation tank in the middle of a West End slum, and in 1814 it exploded.

Henry Meux owned and operated the Horse Shoe Brewery at the corner of Great Russell Street and Tottenham Court Road in London's west side. The tank, made of wood but held together with more than 20 massive iron rings, took up most of the back wall of the building's interior space. The massive barrel held 3,555 barrels of rich brown porter, similar to the stout of today, enough to serve a million people with one pint each. The liquid alone weighed more than 571 tons.

At about 4:30 in the afternoon on October 17, 1814, the smallest of the iron rings fell victim to age and corrosion and snapped. George Crick, the clerk on duty, made note of the breakage, but wasn't overly alarmed, as it happened about two or three times a year, and standard procedure was to simply call someone to come and fix it. However, about an hour later, the barrel violently ruptured, and hot beer burst out of the vat with explosive force. Crick was standing nearby, but by the time he reacted and ran to the barrel, the back wall of the building had been blown out by the sheer power of the rushing flood. The strength of the flood also blasted apart another large vat and several smaller barrels, adding their contents to the torrent. A tsunami of beer, over 7,500 barrels' worth in all, then burst out into the streets of London.

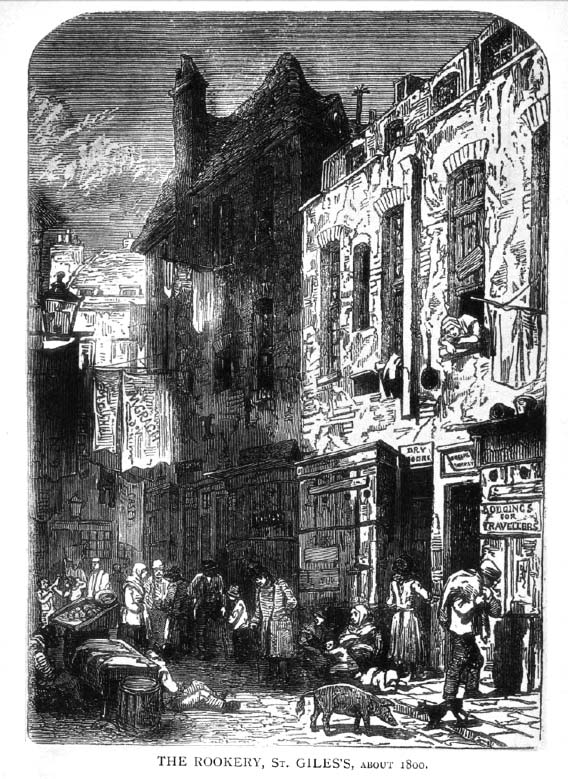

The neighborhood around the brewery was called the St. Giles Rookery, and it was essentially a slum; low-cost houses and tenements housed poor residents, Irish immigrants, criminals, and prostitutes. When the 15-foot-high wave of beer and debris poured into the Rookery, it filled the basements of two nearby houses in moments, undermining and collapsing the structures. In one house, the flood killed Mary Banfield and her daughter Hannah, who were taking tea in their upstairs room. In the other, the rushing beer drowned four mourners holding an Irish wake in the basement for a two-year-old boy who had died the previous day, including the little boy's mother. The flood also knocked down the wall of the nearby Tavistock Arms Pub, crushing a teenaged serving girl beneath it; her body still stood upright when found hours later. In all, eight people were killed (though there was a report of a ninth dying of alcohol poisoning several days later), and two went missing; townspeople wading through waist-high beer rescued three brewery workers (including George Crick's brother, John) and others successfully excavated another from the rubble. The area smelled like beer for months.

Sir Henry Meux

In the aftermath of the flood, locals raised about ₤830 to assist the families of the survivors, who lost an estimated ₤3,000 worth of property. The disaster cost the Horse Shoe Brewery about ₤23,000 (equivalent to roughly ₤1.25 million today) in reparations, and Parliament, by special petition and supported by the Prince Regent, granted Meux ₤7,250 (roughly ₤400,000 today) as compensation for about 7,600 barrels of lost beer. The amount granted by Parliament kept the brewery in business, and Henry Meux later built an expansion. An inquest determined that the flood was an act of God and so Henry was not charged with any crimes; he was later made a Baronet in 1831 by King William IV. The "Beer Flood" also caused the industry to reexamine the use of wooden fermentation vats; during the course of the 19th century, breweries would change over to concrete vats, lined with resin, asphalt, enamel or slate, to prevent just such a calamity from happening again.

The Horse Shoe Brewery was ultimately razed in 1922, and the West End's Dominion Theatre now lies partly on its former site.

Links and Sources:

"Dreadful Accident", The London Times, October 19, 1814, page 3.

"The London Beer Flood of 1814" by Mike Paterson, at the London Historians' Blog, retrieved March 24, 2012.

" A History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 2: General; Ashford, East Bedfont with Hatton, Feltham, Hampton with Hampton Wick, Hanworth, Laleham, Littleton" (1911), pp. 168-178, retrieved March 24, 2012.

The Oxford Companion to Beer, by Tom Colicchio et. al., Oxford University Press, 2011.

A History of Beer and Brewing, by Ian Spencer Hornsey, Royal Society of Chemistry, 2003.

Beer: The Story of the Pint: The History of Britain's Most Popular Drink, by Martyn Cornell, Headline, 2003.

All images are very old and are in the public domain.

"The Beer Flood" © 2015 by James Husband.