On September 25, 1066, at the site of a bridge over the River Derwent in what is now the East Riding of Yorkshire, thousands of Anglo-Saxon warriors led by King Harold Godwinson closed in from the west on a force of Norsemen led by their king, Harald Hardrada. The arrival of the Anglo-Saxon forces took the Vikings by complete surprise. The unarmored and disjointed Vikings frantically organized on the east side of the river, but the Norse king needed more time to arrange their defenses. On the narrow wooden bridge, one lone warrior, his name unrecorded in history, raised his axe and stood defiant against 15,000 English warriors, intent on granting his king and people the time they desperately needed.

Nine months earlier, in January, the English King Edward the Confessor had died without designating an appointed heir. The Saxon Earl of Wessex Harold Godwinson laid claim to the throne, but the Norweigan King Harald Hardrada (meaning "Fairhair") also stated that the title was his by right; a third claimant, far away in northern France, presented a more tenuous claim, supported by an army that posed much less of an immediate threat. Seizing the initiative, Hardrada made a quick alliance with Tostig, the brother of Godwinson and the former Earl of Northumbria, whose title the Saxon king had revoked for mismanagement the previous year, establishing Tostig as an outlaw. Hardrada landed 300 ships in northern England and his army met up with that of Tostig, which had been causing havoc in the northlands for months. The two armies together, along with Flemish mercenaries, numbered between 9,000 and 11,000 men. Godwinson, in retaliation, dispatched the Earl of Mercia and the (new) Earl of Northumbria to muster an army and drive the Norse back into the sea.

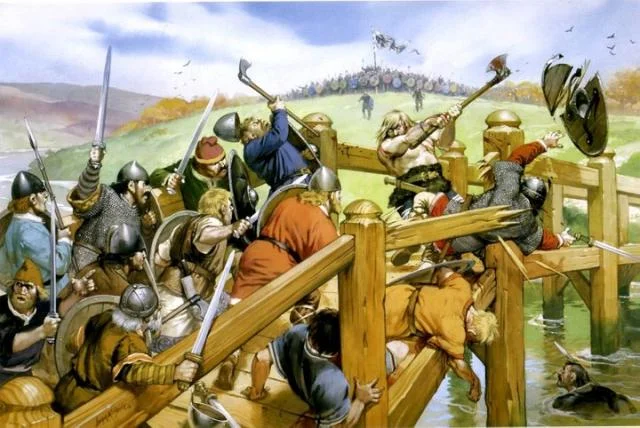

A Viking warrior typical of the time

Hardrada and Tostig, however, dealt this Saxon force a punishing blow at the Battle of Fulford on September 20. Hardrada and Tostig's forces relaxed after their victory, convinced that no serious military threats remained, as Godwinson's army was on the southern coast, more than 200 miles away. Five days later, Hardrada, Tostig, and about a third of their force waited on the banks of the Derwent awaiting a shipment of supplies when, to their surprise, they saw the approach of a new army. As they watched, and saw the ranks of the approaching army grow larger and larger, it slowly occurred to them that they had made a terrible underestimation.

Godwinson, unbeknownst to the Vikings, had force-marched his entire army of 15,000 men, clad in mail and carrying heavy axes and shields, 180 miles in the span of four days, an amazing feat of command and endurance. Norse scouts, if there were any, failed to report the approaching army, and so Hardrada and Tostig did not know that it was in the area until they personally saw approach over a nearby hill. As the day was unusually hot for late September, most of the Vikings had left their uncomfortable and heavy suits of armor miles away on the ships, and the army was scattered haphazardly along the river's edge. Tostig suggested that they retreat to the sea, but Hardrada, realizing that his army would probably be overtaken as they fled, instead ordered his men to make a stand. He dispatched his swiftest riders to Hardrada's lieutenant, Eystein, who had been left to guard the ships.

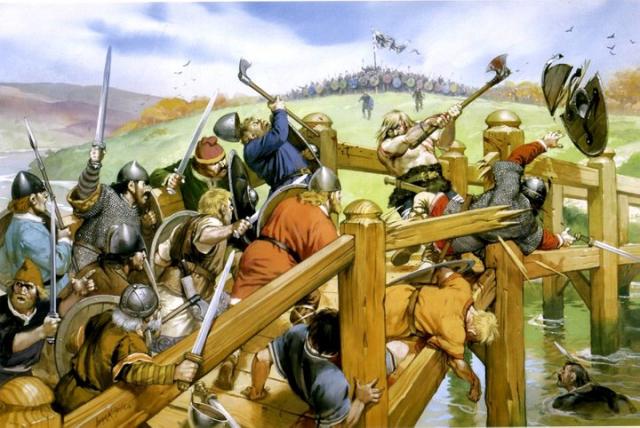

A narrow wooden bridge dating back to Roman times spanned the River Derwent. Hardrada ordered a small contingent of his men to protect this crossing, a mission from which he and they must have known that they would not return. Predictably, they did not appreciably slow down the approaching Anglo-Saxon juggernaut, except for this one lone Viking who refused to yield the bridge. Unlike his companions, he was wearing his coat of mail that day, and was probably also carrying a typically large round Viking shield and wielding an iron axe. He stood at the entrance to the bridge, having killed several of the English, and denied anyone access. Someone called for him to surrender, and assured him that a man of his courage would be treated fairly, but he "with stern countenance, reproached the set of cowards"; sadly, his exact words were not recorded. One English soldier launched a javelin at him, the effects of which he shrugged off; others attacked with swords and spears, but the lone Viking rebuffed their assaults and delivered numerous killing blows. Bodies piled.

Finally, one English soldier climbed into a floating barrel (or possibly a small boat) and let himself drift beneath Stamford Bridge. He found a crack in the aging wood of the floorboards and thrust his spear up through the hole, where the Viking bridge defender continued to stand his ground. Suits of mail in those days were skirt-like, extending down to the thigh or knee, and so this peculiar strike bypassed the Viking's armor entirely. He was impaled in the groin by the surprise attack, and crumpled to the ground. The English army continued across the bridge, after having lost an estimated 40 warriors to the single defender

The delay provided Hardrada and Tostig enough time to form his men into a shieldwall, but the power of the English army overwhelmed their position. English soldiers killed Hardrada and Tostig along with thousands of their warriors. Eystein and his armored reinforcements arrived too late, and the Anglo-Saxon forces them as well. Godwinson spared the life of Hardrada's son Olaf, returning him to Norway to report the defeat. The English had killed so many Vikings that only 24 of the original 300 ships were needed to ferry the survivors back to their homeland. The massive Norse war machine had been smashed, and the Viking Age was effectively over in England.

As for Godwinson, his army, still exhausted from the march and the day's fighting in the hot sun, had barely any time to recover. The third pretender to the throne moved against southern England, and so Godwinson once again called on his Saxon army to march at a dangerously rapid pace. A little less than three weeks later, Godwinson and his exhausted army met their own end near a Sussex town named Hastings, when they were roundly defeated by William, the Duke of Normandy, who would on that day earn the title 'The Conqueror'.

The death of Harald Hardrada at Stamford Bridge

Links and Sources:

England in the Early Middle Ages, by Derek Baker, Boydell and Brewer, 1995.

The Norweigan Invasion of England in 1066, by Kelly DeVries, Boydell and Brewer, 2003.

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, Part 5: AD 1052-1069, available online here.

William of Malmesbury's Chronicle of the Kings of England, as translated by J.A. Giles, Oxford College, 1847.

Painting of the Battle of Stamford Bridge is by Peter Nicolai Arbo, and is available through Wikimedia Commons.

Image of the Viking warrior is from an unknown artist, but appeared in the Osprey Publishing book Warrior 3: Viking Hersir 793-1066.

"The Last Viking" © 2015 by James Husband